The

Redemptive Golf System.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

|

Introduction..........................................................

|

1

|

|

Why The

Fundamentals?....................................

|

7

|

|

The

Set-up.............................................................

|

8

|

|

The Full

Swing......................................................

|

12

|

|

The Shoulders/ Rotator Cuff Muscles................

|

15

|

|

The Rotator Cuff

Exercises.................................

|

18

|

|

The Arms And Hands..........................................

|

20

|

|

The Legs And Feet (Lower Body Action)...........

|

32

|

|

The Laser Guide Swing Training

System..........

|

34

|

|

The

Follow-through.............................................

|

42

|

|

Putting It All

Together.........................................

|

43

|

|

Short

Shots............................................................

|

45

|

|

The Composite Putting System...........................

|

48

|

|

Competition/ Playing Under Pressure................

|

59

|

“It’s

never too late to be what you might have been.”

C

George Elliot (1819-1880), English Novelist.

“If you keep doing

what you always have been doing, then you will keep getting what you always have been getting.”

Source Unknown

“Failing

to prepare is preparing to fail.”

John

Wooden

About the Author:

Dan Blevins is a graduate of Earlham College (Richmond, Indiana)

with a degree in Biology, and California State University (Fullerton, Calif.) with

classes in education and psychology. A four-sport varsity letterer in college

(track, cross-country, baseball, and golf), the four years that he played

varsity golf sparked the beginnings of his intense interest and search to

develop a golf system that would allow him to consistently play at his best. An

avid reader, he used his knowledge in human anatomy/physiology, psychology, and

movement studies, to finally piece-together the system that he had been looking

for all those years. During his senior year in college, Dan was the recipient

of the Wendel M. Stanley Senior-Scholar Athlete Award, named after the school's

1946 Nobel Prize winner.

A resident of Anaheim, California, he has worked both in business

and as a teacher in the Anaheim Union High School District while teaching such

subjects as Chemistry, AP Physics, and advanced math. As a substitute teacher,

he had the unbelievable coincidence of having Tiger Woods in many classes when

Tiger attended Orangeview Junior High and Western High School, which are both

in the Anaheim Union High School District.

His father, Harold Blevins, was born in Topeka, Kansas, and is a

cousin of 5-time British Open winner, Tom Watson, through his grandmother whose

last name was also Watson. Dan modeled his putting stroke after Watson's, which

produces deftly accurate results, and he describes it as being like a person

with a "modern, high-precision, scoped, rifle versus others who are using

18th-Century muskets."

Introduction:

To become the best golfer possible, you

would need to devise a system that would most consistently produce the best swing

technique. It’s an excruciating trial-and-error process that each one must

negotiate, and a never-ending process of refinement of thoughts and procedures

to use when playing on the course. It would be fantastic if we could find

something that said, “Follow these procedures, and use these thoughts, and you

will reach your golfing potential!”

Today, there is no blueprint to follow if you

wish to become the best golfer that you can possibly become. The complex

movements of golf swing technique, and the interplay between the mind (thoughts

and memory techniques) to elicit these movements, present a tremendous

challenge to be solved. Most golfers have gone up and down nearly every

conceivable road—reading the instructional material, taking lessons, watching

videos and telecasts, and more—only to find that they have made little, or no,

progress. Effort and hard work in other fields usually translates into mastery,

but with golf you have to

piece-together, or build, a highly-thought-out swing scheme by sifting through

a sea of information, rather than just learning the whole volume of the

available information. It’s very difficult to discern which roads to take.

J. Douglas Edgar (1886-1921), one of the great players and instructors

of his time, suffered many years of hardship and frustration with his obsession

to master the game of golf. A self-proclaimed duffer of many years, he was able

to assemble a swing system to beat such great players as Tommy Armour and Harry

Vardon, who once said of Edgar, “He will be the greatest of us all.” In his

book, The Gate to Golf, Edgar says, “...my golf career has been

most laborious and I can safely and truly say that if I could have seen ahead,

I probably would not be a golf professional at the present time.” Edgar likened

a golfer’s search for golfing excellence to that of a person “...lost in a

thick fog, walking round and round in a circle, or like a man looking for a

secret door into an enchanted garden, many times getting near it but never

quite succeeding in finding it.”

Edgar stuck with golf because of an inward

feeling that there was a secret in the game, which once found, would enable him

to reach his goals as a player and a teacher. Edgar chanced upon the secret

when he fashioned the idea known as “the gate.” First, he understood the

correct movement at the start of the downswing, and he devised the gate as a

means to insure “the movement.” In essence, “the gate” is three box-like

structures (one can use cigarette packages as a substitute) placed on both

sides of the ball in such a manner that forces the golfer to hit the ball while

the clubhead travels from inside the ball-to-target line. If one does not “hit

from inside-out”, then the clubhead will make contact with the boxes near the

ball. Today, hitting from the inside is considered to be one of the

fundamentals of golf, and it is chiefly due to the insight and work of J.

Douglas Edgar.

Edgar’s secret sufficed for him, but

golfers of today continue to search for a means to push the envelope past the

current level of golf swing technology. The fact that we continue to see, and

use, the same traditional methods and informational sources to teach and learn

the golf swing—including those that were that were used over half of a century

ago—is evidence that we have a long way to go before we have the technology

that will allow us to play consistently to the highest levels of our playing

ability. Anytime we see a large number of remedies for a particular disease

listed in a medical textbook, we can be certain that no remedy is particularly

efficacious; the existence of so many remedies to solve the problem of swinging

a golf club—the enormous variety of instructional methods, the variety of swing

thoughts, etc...—is evidence that we have yet to find a system that is

particularly efficacious. In other

words, we are still far from conquering the elusive nature of the golf swing.

Even the greatest golfers attest to the

elusiveness of this game. Jack Nicklaus states that a golfer never stops

learning, and that one can always get better at this game. In his book, Bobby

Jones on Golf, Bobby Jones calls the game “an inexhaustible subject,” and

he cannot imagine “that anyone might ever write every word that needs to be

written about the golf swing.” Ben Hogan said, “There are nine jillion things

to learn...I don’t think anyone knows all there is to know about the golf

swing, and I don’t think anyone will ever know.” Essentially, most believe that

the swing movements are so complex, and there are so many variables in this

game, that it appears inconceivable that a person can ever get to the ultimate

point of enlightenment and shoot the lowest possible scores and achieve the

highest degree of consistency. Wouldn’t it be great to find one definitive

system that works better than all others?

Inconsistency seems to have become an

integral part of the game of golf. Top players rarely shoot four consecutive

scores that are close to one another, and even the best players rarely win

three, or four, tournaments in the span of a year. In a nutshell, it’s very

difficult to get one’s swing, and the mechanics of the short game, to hold up

for an extended period of time. Even those who have a good understanding of

sound swing mechanics, usually experience a lifetime, push-pull, process of

finding and losing “their game” (even Tiger Woods, after winning The 1997

Masters Tournament by twelve shots, said that it was the first time that he

ever had his “A game” for four rounds). Many just accept the elusiveness, and

inconsistency, of this game saying, “That’s just the nature of this game.”

Today most seek consistency by “pounding” an enormous number of balls on the

range, hoping that the “muscle memory” will allow their swings to hold up on

the course. In addition, many top tour professionals depend on the constant

supervision of a swing “guru,” or highly-esteemed teaching professional, to

help them to maintain sound swing technique.

Current instructional methods, and swing

schemes, are insufficient to guarantee a high degree of consistency. We already

have the swing figured out—it’s basically the same series of movements— but future

advancements in golf will come from the development of the best memory

techniques, and swing training techniques, that will allow you to consistently shoot

lower scores.

There are basically a few reasons that it

is very difficult to successfully negotiate the process of becoming a fine

golfer. First, the golf swing is extremely difficult to analyze and to

understand because it is a complex amalgam of movements (rotation, vertical

lift, etc.) that occur simultaneously, and in sequence; In other words, it is

very difficult to see and understand the individual movements (hands, arms,

shoulders, etc.) when everything moves so fast, and at the same time. Second,

there is a massive amount of instructional material that can lead to great

confusion; it can seem like there are a million different ways to swing the

club, when everyone is actually trying to describe the same series of

movements. Third, the human mind (memory) has limitations that make it very

difficult to have a firm grasp of the golf swing. Even though one may have a

deep understanding of sound swing technique, it is very difficult to retain and

to reproduce on the golf course. Thus, to progress to a high level of playing

proficiency, each golfer must first complete the arduous task of learning sound swing mechanics, and then the

equally-arduous task of finding the best swing thoughts that will allow the

most consistent reproduction of these mechanics.

“Low and slow," "Take it back on

line," and "Get it into the slot (at the top)" are a few of the

common swing thoughts that have been used for many years. However, the problem

with these thoughts, and most instruction given in articles, books and videos,

is that they are nebulous and imprecise directions to swing the golf club. For

example, it's very difficult to take the club back on an imaginary line, and

usually the club is taken inside, or outside, of the line. Also, "low and

slow" usually is exaggerated and the golfer sways, moves the head, and

throws the weight too far on the outside of the right foot. An instruction such

as, “get your left shoulder underneath the chin,” does not ensure a correct

shoulder turn. Also, many swing thoughts, and instruction, work as remedies in

the short-term, but often they become exaggerated, or misconstrued, over time and

present the golfer with additional problems. In addition, since the human mind

has a limited focus, the narrow range of these swing thoughts only allows for a

limited degree of control and consistency.

If people were strictly biochemical

machines, with brains analogous to complex computers, then the methods of

science could be utilized to find the best system that would consistently

produce the best results. Everyone could play like a machine, which would

produce the same sound technique, and any error, or inconsistency, most likely

would be due to environmental factors, the golfers’ judgments, and differences

in physical abilities.

However, unlike the action of a machine,

golf is a human enterprise and not strictly an objective mechanical process.

Sure we can make objective measurements, and descriptions, of the swing, but

the subjective concepts of the mind—the origins of the swing—are not yet

amenable to scientific inquiry. Someday, we will be able to evaluate the

effectiveness of swing thoughts, and memory techniques, and devise

swing-training systems, and swing schemes, that will be far superior to those

of today; we will then be able to take a short-cut, by eliminating the

tremendous volume of instructional material and the amount of time testing this

material, and become fine golfers in a

much shorter interval of time; in other words, this material could serve as a

blue-print for those with the dream of realizing their potential. Until this

revolution in swing training technology occurs, most golfers will continue to

learn the game in the traditional manner—and experience all of the confusion, wasted

time, limited success, and inconsistency that come along with this process.

To go beyond the limits of today’s

training methods, and swing concepts, we will need to design a swing system,

composed of carefully-devised swing thoughts that will push the limits of the

human mind and allow the highest degree of control, and consistency, in the

production of sound swing mechanics. By devising swing thoughts that encompass

many swing variables, we can gain tremendous control over the golf swing!

About thirty-five years ago, I started

using a scientific notebook—much like the one I used in my college chemistry

and physics labs—to help in the development of my game, and in the search to

develop material that would go beyond the limits of traditional, and existing,

swing concepts (I wanted to develop a system that would give me a competitive

edge over other players). I called this notebook my “range book” and I used it

mainly to record, organize, and evaluate swing thoughts and set-up positions. I

recorded lists of exact-word swing thoughts, and descriptions of swing

movements, of a great number of the top teachers and players. In addition, I

included my own original swing thoughts, especially ones that were devised from

watching other golfers. Next, I tested these thoughts, and made different

arrangements of the most effective information, visualizations, and thoughts.

My goal was to formulate a system—a swing scheme—that would allow me to shoot

the lowest possible scores and achieve the highest degree of consistency.

In the following pages, I will present a

revolutionary swing training system designed to lead to the understanding and

the consistent execution of a sound golf swing. This system is based on years

of research in physiology, biomechanics, psychology, and learning and memory

technology. I have designed this system to circumvent the problems of

traditional swing training methods by incorporating conceptual images that lead

to a high degree of technical understanding and the ability to produce a higher

degree of control and consistency. To achieve this, we first must gain an

understanding of the exact location and function of the muscles of three very

important areas: the left hand and arm, the right hand and arm, and the

shoulders. These three areas are part of a three-point focus that is the secret

to a sound swing and tremendous consistency—it is the foundation of this

system. Such concepts as lower-body movement (e.g., weight shift), constant

spine angle, keeping the head still and behind the ball, and many others, have

been practiced for many years and have become “second nature” (or at least,

subconscious); thus, we can narrow our focus to these crucial areas: the action

of the left and right arms, and the shoulders. Most golfers often understand

these three areas vaguely and we can gain great control, and the understanding,

to produce a sound swing if we focus down to the anatomical level—muscle groups

and their specific functions. In addition, I will present many key thoughts and

visualizations to facilitate the understanding of the individual swing

movements and I will teach one to incorporate these movements into one smooth

swing. These concepts will not only be

used to give one a greater understanding of the swing movements and to ingrain

these movements into “muscle memory” before one steps foot on the course, but

they also serve as swing thoughts to ensure the correct execution of the golf

swing on the golf course. Thus, I’ve designed this system to allow one to

control a tremendous number of swing variables—simultaneously—which goes far

beyond the degree of control that one can attain with the use of traditional

swing training systems, or the use of individual swing thoughts.

I’ve named this system “The Redemptive

Golf Swing” because it is designed to allow golfers to achieve higher levels of

playing ability, after years of being stuck in the same “rut.” Golf is one of

those games where dedication can be spent to countless hours of playing and

practicing, year after year, yet no improvement in playing ability may be

realized. This system will allow one to move forward. I have purposely tried to

refrain from restating all of the sound information that can be found in most

books on the subject, such as the intimate details of the grip, the set-up, and

other fundamentals. Restating all of this information would only make this work

more laborious and confusing—and redundant to those who have read it countless

times!

“If you keep doing what

you always have been doing, then

you will keep getting

what you always have been getting.”

—Source

Unknown

References:

1.) Edgar, J. Douglas. The Gate To

Golf. 1920. Published privately in Washington, D.C.

2.) Jones Jr., Robert Tyre. Bobby

Jones On Golf. 1984. Golf Digest Inc.

Why

the Fundamentals?

The scientific method has allowed us to

accrue a list of fundamentals (e.g., a straight left arm, a straight and constant

spine angle, a steady head, the Vardon grip, etc.) that produce a more

efficient swing and thus more consistent results. After decades of

trial-and-error testing, these fundamentals have been accepted into theory as

the best means to swing a golf club. These fundamentals are the base upon which

any swing advancement must be built. Just as Isaac Newton said that he stood on

the shoulders of giants (his scientific theories were built upon the theories

of his predecessors), a swing must stand on the shoulders of these

fundamentals. Anyone who tries to develop a swing, and ignores these

fundamentals, is only making the process more tedious, lengthy, and difficult.

The ideal scenario would be for one to

focus simultaneously on all of the fundamentals. Since the human mind does not

have the capacity to focus sharply on all of these points at the same time, the

closest that we can come to achieving this ideal is to devise a concise swing

system that integrates these fundamentals into a narrower focus. In short,

advancement in swing technology must include key thoughts and visualizations,

and other memory techniques, which allow golfers to consistently achieve the

fundamentals of a sound swing. We are not looking for a different swing, but

merely the best visualizations and groupings of swing thoughts that will allow

us to reproduce the swing more often.

“When your game has a solid

foundation and you don’t have

to rely on luck, you

make your own breaks.”

—

Gene Littler

The

Set-Up:

A large volume of good instruction has

been written on sound grip and set-up principles. Ben Hogan's book, Five

Lessons: The Modern Fundamentals Of Golf, thoroughly covers these

principles and is an excellent reference. Also, Jack Nicklaus's book, Jack

Nicklaus, The Full Swing, gives excellent pictures and instructions to

guide one in achieving a proper grip and set-up. A sound grip and set-up are

the foundations upon which this swing system is built. By properly gripping the

club and placing one's body into sound positions, the muscles can work in

unison to produce a fluid and repeating golf swing. Everything in the body is

connected, through a series of muscles, tendons, and bones; if one segment of

the body is out of position, it can ruin the entire swing.

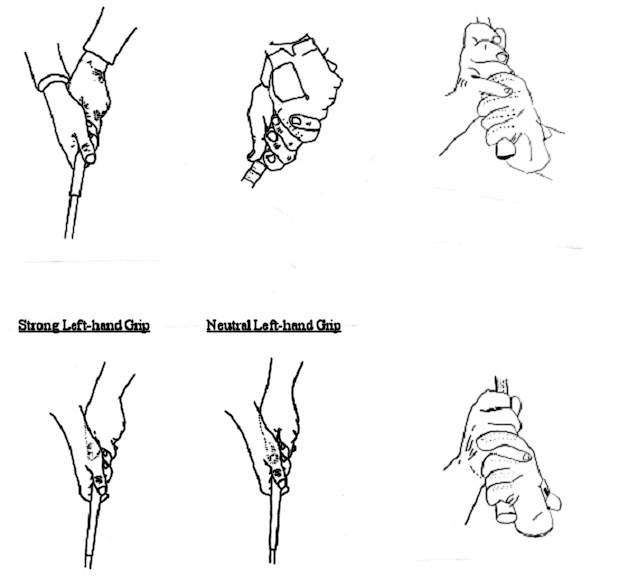

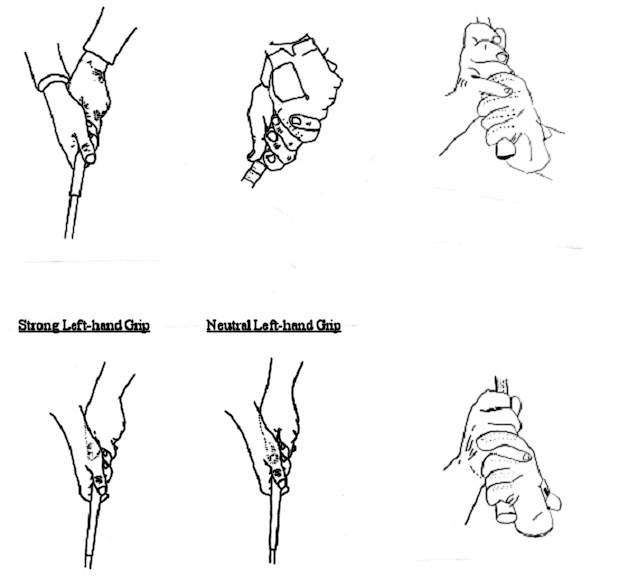

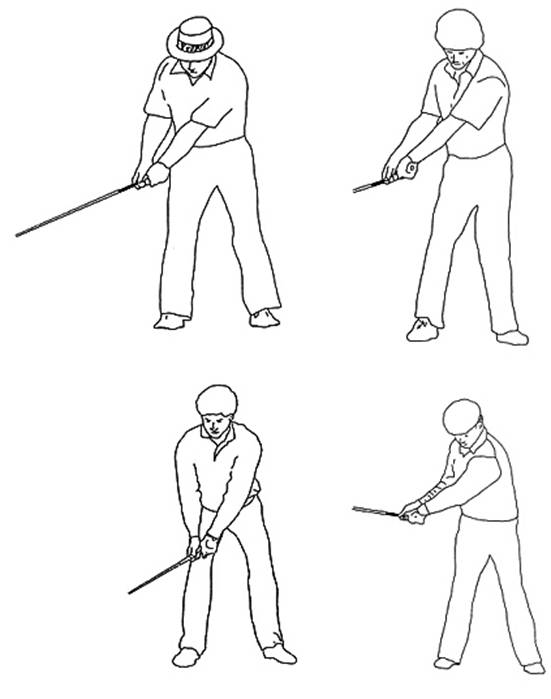

The goal of the golf grip is to place your

hands in a manner that will allow the consistent production of the desired shot

(see figure 1). The modern grip techniques (the Vardon, the interlocking, and

the ten-fingered) allow maximum control of the shot, because they reduce the

influence of the small, tough-to-control, muscles of the hands and arms. This

is achieved because the hands are placed on the club so that they oppose one

another; this nullifies the influence of the hands and allows the larger

muscles of the shoulders, arms, and legs to control the swing. These larger

muscles are less prone to “twitchy”, or jerky, undesirable movements, that could

result in disaster on the golf course.

Your left hand should grip the club so

that most of the pressure is in the last-three fingers (the ones furthest from

the thumb), and the club should be balanced by running it up into the “butt of

the palm.” Your left wrist should arch downward, which allows it to serve as a

strong link that will not break down at impact.

In the Vardon and the interlocking grips,

the right hand is placed so that the ring finger (the finger next to the

“pinky”) runs snugly up against the index finger of the left hand. Also, the

right hand is a finger grip, with the club mainly held by the middle-two

fingers of the right hand. In addition, the right wrist should also arch

downward. We can gain maximum control of the golf ball by placing the hands,

fingers, and wrists in these positions.

The “V’s” formed by the thumb and the

forefinger should point toward the seam of the right shoulder. If the “V’s”

point to the outside of the right shoulder this will promote a closed clubface

at impact which will result in shots that go to the left for a right-handed

golfer. If the “V’s” point to the inside of the right shoulder (a little more

towards the left shoulder), then this will promote an open clubface and shots

will tend to go to the right.

The slightest change in the golf grip can

greatly influence one’s golf swing. Gary Player said that he was about a

6-handicapper, compared to the average touring professional, when he first left

South Africa to play in the British professional events. He attributed an

alteration in his grip (he moved his left thumb more toward the right side of

the shaft) as one of the main reasons that he was able to improve and

eventually win important tournaments. He arrived with a very flat swing and an

excessively weak grip (the thumb was on the left side of the shaft), but with

insight, and a tremendous work ethic, he was able to fix these problems.

Arm placement is another important set-up

principle. The arms and hands are the links that allow the body to transmit

power and control to the club. Just as with the hands, improper placement and

use of the arms will result in a loss of power and control. The goal of the

grip is to unify the hands to perform as one; the arms should also be positioned

to perform as a unit.

The arms should be held close together,

and the upper-portions should be pressed against the upper-torso. To ensure

against any independent action of his arms, Ben Hogan imagined that they were

held close together by being wrapped with rope, or twine. He also focused on

using only the inside muscles of the arms. Any movement of the upper arms, away

from the body, will destroy the unified action of the arms and the link between

the body and the club head.

Another important fundamental is to set-up

with a straight spine that is maintained at a constant angle to the ball,

throughout the swing. Many golfers accomplish this task by visualizing the

spine as a straight post, which runs from the base of the neck to the tailbone.

One then swings the club around this central axis (the post), by shifting the

weight back and forth while maintaining the straight spine. A straight spine is

essential because it allows the golfer to get the club back to the address

position, and thus to swing the club in a consistent manner.

The following are important swing principles that one should have

ingrained into memory:

· Left hand (club goes

up in pad of palm)/right hand (fingers).

·

Use the inside muscles (legs and arms).

·

Hold the arms close together, with the upper segments in

close contact with the upper torso.

· The arms should hang

straight down over the feet.

· Weight shifts to the

right and behind the ball during the backswing, and back to the left side for

the downswing.

· Keep the weight on

the insides of the feet.

· Swing around the

straight spine (the central axis).

· Keep the head still.

References:

1.)

Hogan, Ben. Five Lessons: The Modern Fundamentals Of Golf. 1957. Simon

& Shuster. N.Y., N.Y.

2.)

Nicklaus, Jack. Jack Nicklaus, The Full Swing. 1982-1984. Golf

Digest/Tennis Inc. Trumbull, Ct.

Figure 1— Illustrations of the golf grip. In the left hand,

the club runs from the index finger and is pushed up into the “butt of the

palm” near the end of the club; the thumb is placed near the top of the club’s

grip and most of the pressure is in the last-three fingers. The right hand is

considered a “finger grip,” with the middle-two fingers providing most of the

support, or pressure. The idea is to have a “palms-facing” grip so that the

hands can work together as one unit.

There are several variations of the grip. First, the overlapping (the

Vardon), the interlocking, and the ten-finger grips are variations that are

characterized by the placement of the “pinky” of the right hand. Second, the

hands are turned to the right of the neutral position in the strong grip, while

a weak grip has the hands turned to the left of the neutral position. Usually,

the stronger grips produce a “draw,” or “hook,” and the weaker grips produce a

“fade,” or “slice.” The bottom left (two) grips illustrate a strong left-hand

grip (thumb placed more on the right side of the shaft), and the left hand

placed in a weaker position.

The

Full Swing:

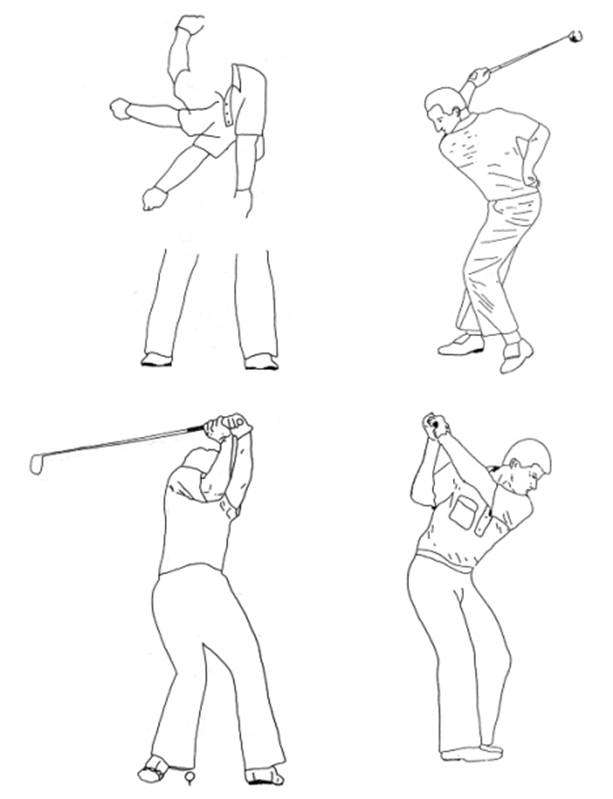

By studying the progression of Ben Hogan’s

golf game, we can gain great insight about the process of becoming a highly

skilled golfer. In the early years of his career, Ben was a struggling

professional plagued with a loose and highly unreliable swing. However, through

an uncanny power of observation and the ability to study and test information,

he was able to develop a golf swing and a rock-solid swing scheme that enabled

him to become one of the greatest players in the history of the game. He had a

thorough understanding of all aspects of the swing—the exact set-up positions,

and the exact muscles to use— which enabled him to piece together a swing

scheme that did not fall apart under pressure.

After years of searching for “a secret”,

or means, to increase accuracy and consistency, Ben Hogan devised his

plane-of-glass visualization. He visualized a plane of glass that ran from the

ball through the mid-point of his shoulders, and he imagined that his arms

brushed up against this plane as they went to the top of the backswing. By

doing this he attained the same swing plane and arc for each swing, which was

the key that allowed him to attain a tremendous level of consistency.

While I was developing my game and working

as a substitute teacher, Tiger Woods was in many of my classes from the time he

was in the seventh grade until he graduated from the twelfth grade at Western

High School. I was amazed that this kid, whom I first saw in a seventh grade

math class at Orangeview Jr. High School, was considered the best player of his

age in the world and that he could beat the best high school players in Orange

County, who were four to five years older.

I believe that Tiger became such a fine player at such a young age,

because of his early, and year-long, regime of daily practice, weekly lessons,

and playing in as many tournaments as possible. Through all of this, he became

extremely comfortable in tournaments, he developed superior technique, and he

found memory techniques to reproduce it on the course. Even though he was much

younger than many of the golfers he competed against, he was essentially a kid

with the technique of a touring professional (his first professional

instructor, Rudy Duran, said that he was essentially a ‘shrunken touring

professional’ at the age of six). I remember watching him tee off at The

Cypress Golf Club during one of his high school matches, and soon after he

pointed to, and turned, his shoulders in a very specific manner saying, “It

goes like this.” He had a very precise visualization, or memory technique,

which allowed him to consistently produce the correct shoulder turn. Over the

years, I’m sure that he picked up memory techniques for all of the shots, and

the individual movements of the swing—all of which is the software that allows

him to play as well as he does today. Most of golf is technique, and he had a

means to reproduce this technique at an early age.

One of the main reasons that Tiger was

able to progress to his current level of play was because his entire game was

built on sound positions, and fundamentals (In an interview of 1997, Jack

Nicklaus said, “Tiger Woods has the best fundamentals that I’ve ever seen.”).

By placing the parts of his body in the same sound, time-proven, set-up

positions for each shot, he maximizes his chances of hitting the desired shot.

You have to have a first-rate grip and set-up, if you hope to play anywhere

near Tiger’s level of play. We’ve seen many touring pros “push” their games to

much higher levels in efforts to compete with Tiger Woods, and the first part

of this process was to make sure that they had the best possible fundamentals

and set-up positions. You can’t beat a repeating machine at its task, unless

you make adjustments to become more efficient than that machine!

The best players have at least one thing

in common: each has a highly-detailed understanding of swing dynamics. At this

level, there is no such person as the so-called “natural golfer” (one who can

play the game well without any hard work, or deep thought). No matter how much

one tries to simplify it, the golf swing is an unnatural, complex, motion that

must be meticulously studied if one is to attain a high level of proficiency

(the great golf instructor, Alex Morrison, called teaching the golf swing “one

of life’s most difficult callings...due to the fact that the correct positions

and movements are the exact opposite of what anybody would do instinctively.”)

A person with superficial knowledge of the swing, or who mainly relies on

“feel,” is at a great disadvantage when compared to a person with Hogan-like

knowledge. The key to making “shot after shot”, especially in extreme pressure

situations, is to learn a system to consistently produce a sound golf swing;

this can only come about by meticulously studying the details of all aspects of

the swing. If you wish to consistently

beat your playing partner, you have little chance unless you have at least

equal, or better, fundamentals and swing technique.

Players like Sam Snead, Lee Trevino, Fred

Couples, and Seve Ballesteros, appear as though they could be labeled “natural

golfers.” They may look like they play the game by “feel” and without mental

effort, but any of these players could talk all day on the most intimate

details of the swing. Talking to Lee Trevino about the effects of shafts and

other club components, is like talking to an aeronautical engineer about air

flow dynamics, wing configuration, and airplane performance. Sam Snead and Seve

Ballesteros had such profound understandings of the cause-and-effect

relationships of set-up positions and certain swing movements, that each has

been able to use this insight to attain such labels as “the greatest shotmaker”

and “the greatest short game player” of all time, respectively. These people

always had swing thoughts and information going through their minds, and poor

play could usually be attributed to poor

concentration in these areas.

“The man who can

consistently hit the ball close to perfection without

thinking deeply about

what he’s doing hasn’t been born yet, and never

will be.”

— Gary Player

“You aren’t born with a

club in your hand, you have to manufacture

a swing.”

— Ben

Hogan

The

Shoulders/ Rotator Cuff Action:

To attain consistency, you must have a means

to consistently produce the individual movements that make up the swing. Thus,

it’s extremely important to have a method to ensure the correct shoulder turn.

The following are some swing thoughts to turn the shoulders from various

sources:

· “...bring the left

shoulder under the chin to a position behind the ball.”

· “...hips and

shoulders are to start turning away from the ball...”

· “...the left shoulder

should pass under the chin and your back should be facing the target.”

· “...the body turns

like the hub of a wheel.”

· “...your shoulders

turning on the same plane as your hips.”

· “...throughout the

swing...the shoulders retain the same ratio to the ground.”

· “The left shoulder

...moves transversely...away from the ball.”

Rather than offering worded instructions

to turn the shoulders, much of the literature simply tells one to turn the

shoulders, or states that the shoulder turn is an unconscious phenomenon that

occurs naturally in response to the swinging of the club.

It’s very difficult to describe the

kinesthetic (muscular) sensations that occur when one swings the club, and it’s

even more difficult to describe these in such a manner that other people can

understand and use these in the development of their game (this is probably the

foremost reason that there is so much instructional material). The nebulous

nature of this material, and the fact that I could not find something that I

could absolutely rely upon to ensure a correct shoulder turn, led me to search

for something better. I studied the individual muscles of the shoulder area,

and developed a system to activate the specific shoulder muscles which ensured

the consistent execution of the correct shoulder turn. All one needs to do is

to understand the location of these muscles, learn to feel the location of

these muscles, and then learn to activate these muscles during the swing.

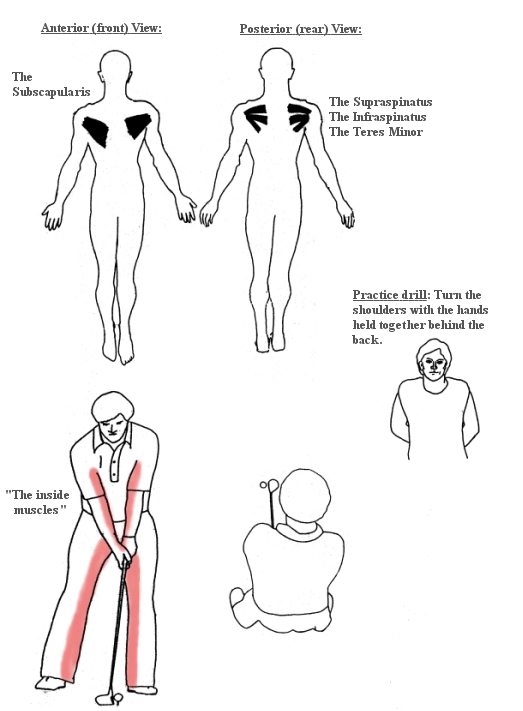

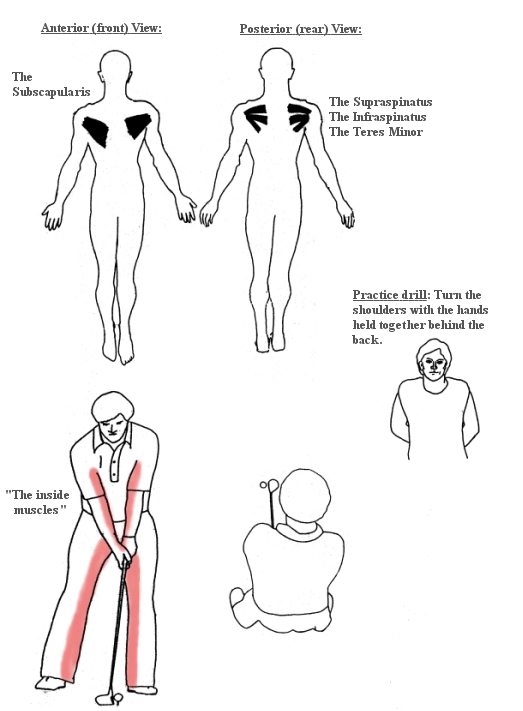

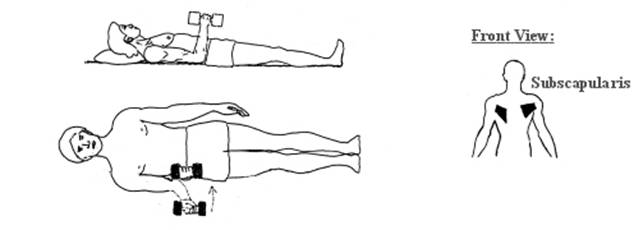

Physiological research has revealed that

the rotator cuff muscles (a group of four muscles that are located on the front

and back of each shoulder) produce the force to correctly turn the shoulders in

the golf swing (see Figure 2). We can consistently produce the correct shoulder

turn by isolating, and learning, the action of the rotator cuff muscles. By

focusing down to the anatomical level—visualizing the rotator cuffs turning the

shoulders back and forth—we can eliminate a multitude of variables that are

responsible for inconsistent shot making. Instead of some unreliable swing

thought to swing the club back (e.g., "get the left shoulder under the

chin"), we have a precise method to ensure the correct rotation of the

shoulders. All one has to do is isolate these muscles, and learn to consciously

activate them to control the shoulder turn.

Muscles move the body by contracting

(shortening), and thus pulling tendons and bones. The rotator cuff muscles

rotate the shoulders by pulling one shoulder outward, and the other shoulder

backward. For example, for a right-handed golfer, when the rotator cuff muscle

at the front of the left shoulder contracts, the left shoulder swings outward;

when the rotator cuff muscles in the back of the right shoulder contract, the

right shoulder swings backward. Together, equal-force contraction of these

muscles result in a perfect rotation of the shoulders for the backswing of a

right-handed golfer. The forward swing requires equal-strength contraction of

the right-front, and left-rear, rotator cuff muscles.

More specifically, the rotator cuff is

comprised of one large muscle on the front of each shoulder, and three smaller

muscles located on the backside of each shoulder (see Figures 2 and 8). There

are several exercises that you can do to strengthen these muscles, and the

next-day soreness will give you a good idea of the muscle locations (see

“Rotator Cuff Exercises”). By strengthening these muscles, you can increase the

chances that they will control the shoulder turn over other muscles. A good key

for repeating the same shoulder turn is to focus in on turning the shoulders

back, and through, with the rotator cuff muscles. Over time, these movements

will be ingrained into “muscle memory” and will become

"second-nature" during the swing.

A good method to practice the proper

shoulder turn is to swing the shoulders, back and forth, with the hands held

together behind the back. Concentrate on turning the shoulders around the

fixed-axis of the spine, while shifting the weight back and forward (to the

insides of the feet) in the proper sequence. When shoulder-turn problems occur

on the course, visualization of this drill will help you to get back to the

proper shoulder turn.

Figure 2— Anterior (front), and posterior (rear),

views of the rotator cuff muscles. One muscle, The Subscapularis, is located at

the front of each shoulder. This muscle is underneath The Anterior Deltoid and

The Pectoralis Major. Three muscles (The Supraspinatus, The Infraspinatus, and

The Teres Minor) are the rotator cuff muscles on the posterior (rear) side of

each shoulder. The Teres Minor is a superficial muscle (closer to the skin

surface) and The Supraspinatus and The Infraspinatus are located at positions

deeper in the shoulder.

Rotator

Cuff Exercises:

Now that you have learned about the

location and function of the rotator cuff muscles, this section will show you

how to strengthen these muscles, feel their location, and learn to activate

them to produce the correct shoulder turn. You can achieve these objectives by

doing rotator cuff exercises. These exercises are the link that will allow you

to activate the correct shoulder turn, at will, on the golf course!

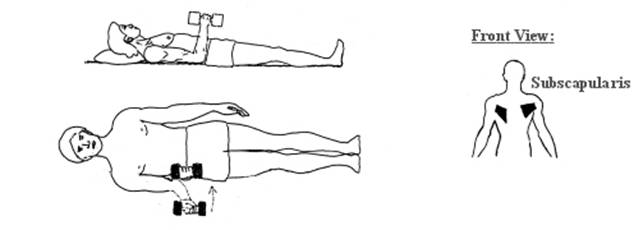

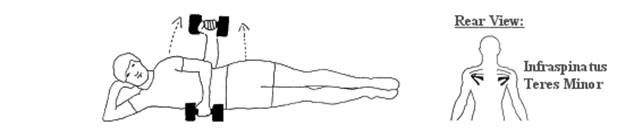

The following are three exercises to

strengthen the muscles of the rotator cuff: 1.) External Rotation (Teres

Minor and Infraspinatus); 2.) Internal Rotation (Subscapularis); 3.)

Elevation (Supraspinatus). Do the same number of repetitions on both sides,

to ensure that one side does not become more dominant than the other.

The purpose of the rotator cuff exercises

is several-fold: First, strengthening these rotator cuff muscles will ensure

that these muscles control the shoulder turn over other muscles such as the

Deltoid; Second, equal strengthening of both sides will protect against an

incorrect turn which could occur if one side was stronger than the other;

Third, next-day soreness, and awareness of the position of these muscles during

the exercises, will allow you to feel and to understand the location of these

muscles; this will allow you to focus upon the location of these muscles, and

to call upon them when executing each swing.

In addition, there are countless sites on

the internet (in both writing/pictorial as well as video format), that can be

found in the search engines to strengthen and stabilize the shoulders. Some of

these exercises are “static exercises”, others can use lightweight dumbbells,

elastic bands, and specialized “gym-type” equipment. Some common search engine

keywords would be shoulder stabilization exercises, rotator cuff exercises,

shoulder stability, etc…

Exercise

1: Rotator Cuff—Dumbbell Internal Rotation.

Technique: Lie with your back flat on

the floor, press the upper arm against your side, and bend your elbow to form a

90-degree angle. While keeping the upper arms pressed against your side and the

floor, slowly lower the dumbbell close to the floor and then raise it until it

is pointing straight upward at 90 degrees to the floor. Repeat 10 times and

then change sides.

Technique: Lie with your back flat on

the floor, press the upper arm against your side, and bend your elbow to form a

90-degree angle. While keeping the upper arms pressed against your side and the

floor, slowly lower the dumbbell close to the floor and then raise it until it

is pointing straight upward at 90 degrees to the floor. Repeat 10 times and

then change sides.

This exercise strengthens The Subscapularis muscle, which is located at

the front (anterior side) of each shoulder.

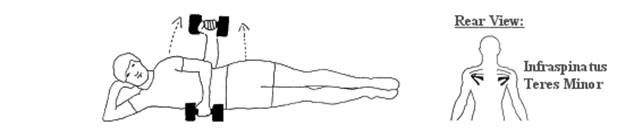

Exercise 2: Rotator

Cuff—Dumbbell External Rotation.

Technique: Lie on your side as illustrated.

Press the upper arm against the side and on line with the shirt seam. Bend the

elbow to form a 90-degree angle. Slowly lower the dumbbell toward the floor and

then slowly raise it until your arm is pointing straight upward. Repeat 10

times, and then change sides and do the same with the other arm.

This exercise strengthens The Teres Minor and The Infraspinatus muscles,

which are located on the back (posterior side) of each shoulder.

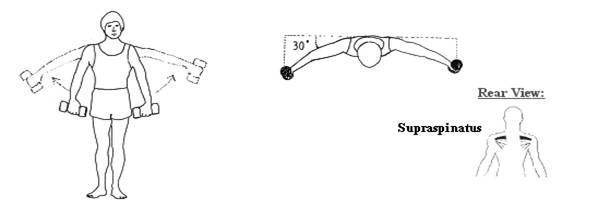

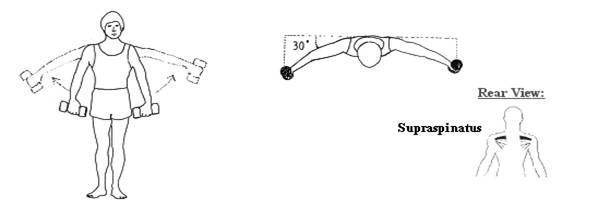

Exercise 3: Rotator

Cuff—Dumbbell Elevation.

Technique: Hold the dumbbells with the back of the hands (the side

opposite the palm) facing forward and the thumbs pointing toward the floor.

With straightened arms angled out at 30 degrees to the shoulder plane, slowly

raise the arms to just below shoulder level with the thumbs continuing to point

downward. Do not go up to shoulder level or higher, since this could result in

injury. This exercise strengthens The Supraspinatus muscles which are located

on the posterior (back) side of each shoulder.

To summarize, this section presented a

carefully-devised system to ensure a

correct shoulder turn. First, we learned that the rotator cuff muscles (one

located at the front of the shoulder, and three on the back) pull one shoulder

outward, and the opposite shoulder backward, to produce the correct shoulder

turn. Next, I presented the rotator cuff exercises as a means to not only

strengthen these muscles, but also as the avenue to become familiar with the

sensations, and locations, of these muscles. The ultimate goal is to be able to

summons these muscles, time after time, to produce the correct shoulder turn.

The Arms & Hands:

Now that you have a detailed understanding

of the shoulder turn, this section will complete the three-point focus by

presenting the details of the left-arm, and the right-arm, action. While the

shoulders rotate the club backward during the backswing, the hands and arms

contribute by lifting the club upward (the vertical component). The blending of

these two motions (rotation and lift) produce a smooth arc that is typical of a

sound swing. The combined motion of both arms is nearly identical to a

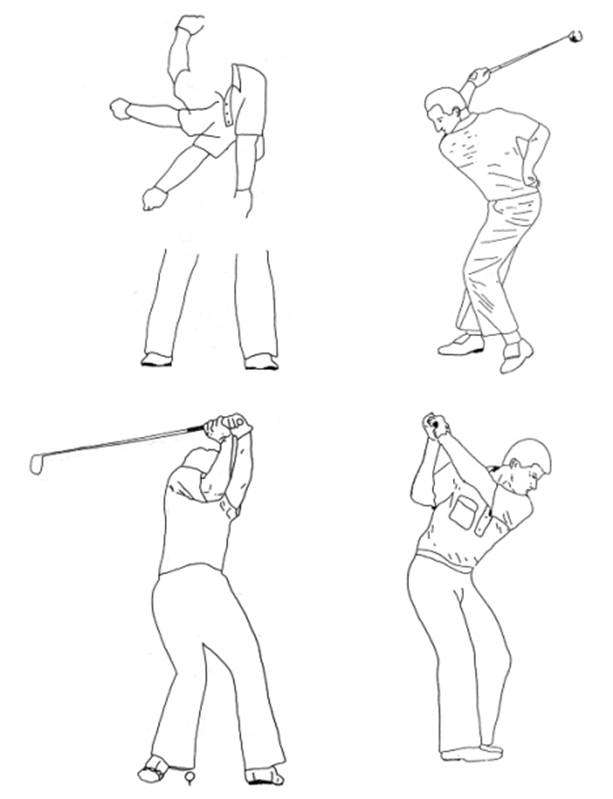

lumberjack's straight, over-the-head, chopping motion with an axe.

We can see, and understand, the correct

left-arm motion by studying the details (the path of the arm , the tensions in

the muscles, etc…) as one swings the club to the top with only the left hand

and arm (see Figure 3). When viewing the left arm in this manner, it is

apparent that it remains nearly straight and that it functions to keep the club

in “a square position” throughout the swing. Often, Tiger Woods swings the golf

club with only his left arm as a practice drill before he hits a shot on the

golf course. Apparently, he has found this drill as a reliable means to

consistently produce the correct left-arm motion.

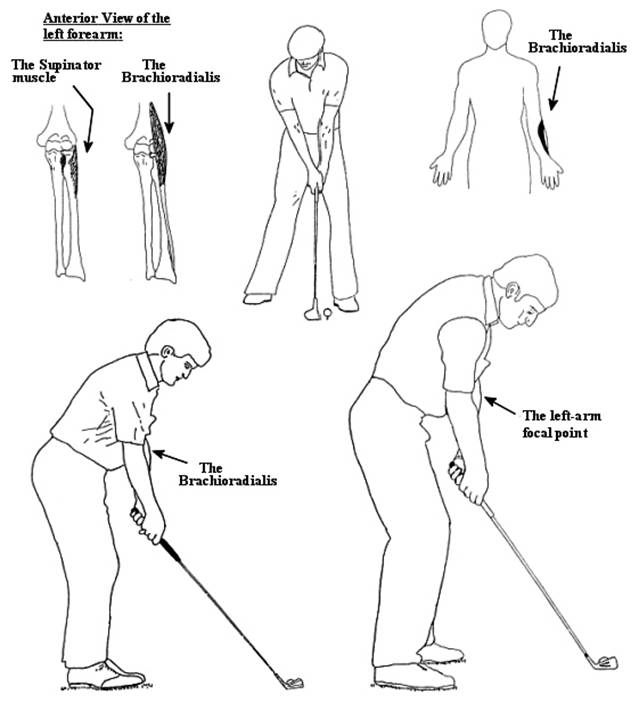

The Triceps and The Anconeus muscles

extend the elbow and thus straighten the left arm. These muscles are located in the posterior

region of the arm, since they pull in the opposite direction of the flexor

muscles located on the anterior side of the arm.

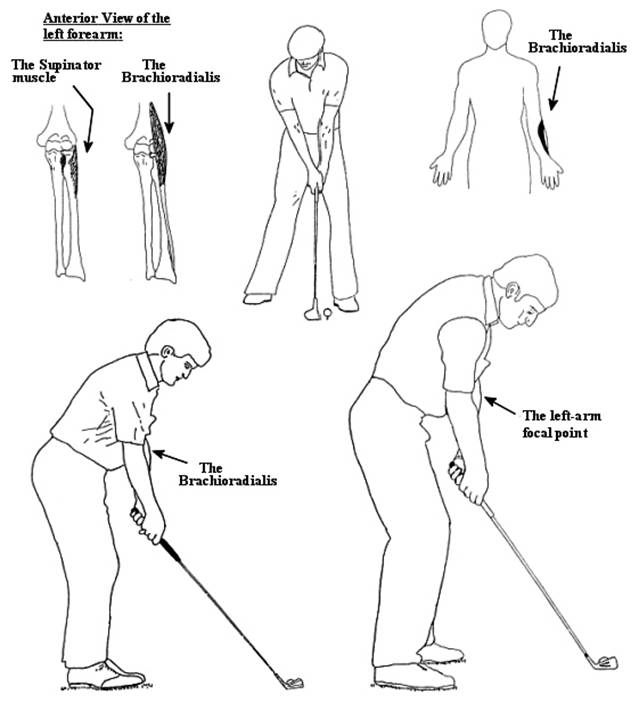

Figure 4 illustrates an area, near

The Brachioradialis of the left forearm, which I call “the left-arm focal

point.” If you watch the swing of a professional golfer from directly behind

(near an extension of the target line), the function of this area becomes more

apparent. I’ve found that the correct left-arm action can be achieved by

focusing in on this area, at the start of the backswing. Not only does the left

arm remain straight, but this focus keeps the club in a square position as it

goes to the top of the backswing. The

muscles of the radial and posterior brachial regions, which comprise all the

extensor and Supinator muscles, act upon the forearm, wrist, and hand to keep

the club in the perfect position during the swing. The Supinator and the Biceps

Brachii muscles act as direct antagonists of the rotational force of the club

and arms, which would move the arms and swing the clubhead well inside of a

“square” position. In other words, these muscles act to gradually counteract

the tendency of the rotational force to pronate the left arm during the swing;

they keep the hand and arm in the same position as at address, which is the

position they would naturally occupy when placed across the chest—the prone

position, or the position of action.

Professionals concentrate on keeping the

left arm straight, because it allows them to consistently get the club back to

the address position at impact. Breaking the left arm, or bending it at the

elbow, will result in all types of mishits (e.g., “fat” and “thin shots”) because

there will be no precise key to enable one to get back to the ball. A straight

left arm gives the golf swing a constant radius, and thus it is a very

important fundamental. This is the key that trick-shot artists focus upon to

hit the ball with unbelievably long, and “whippy”, shafts.

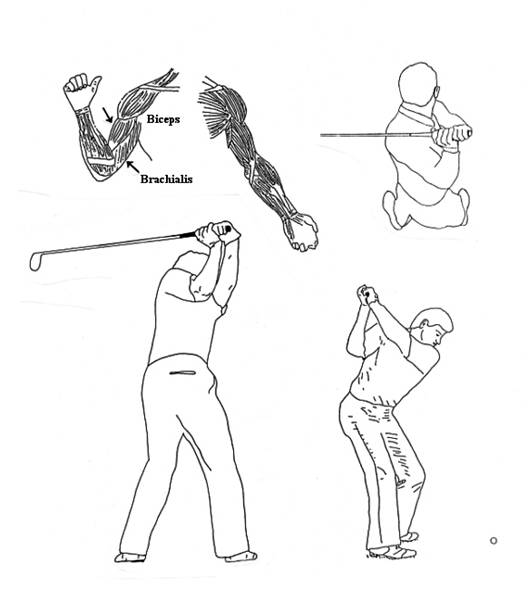

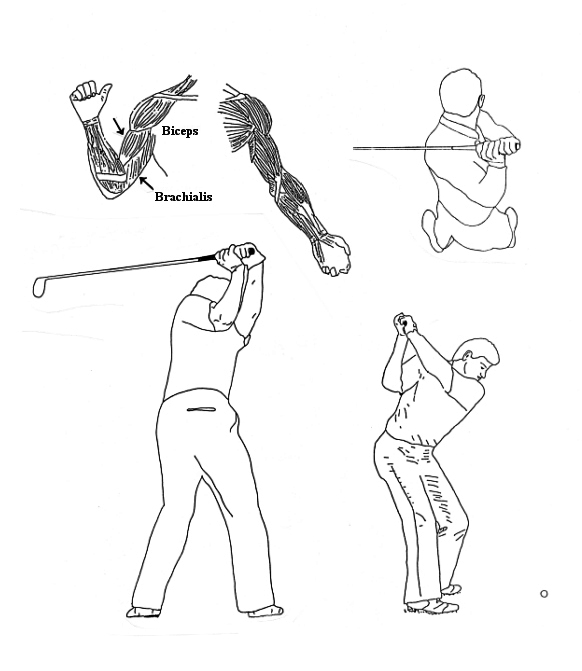

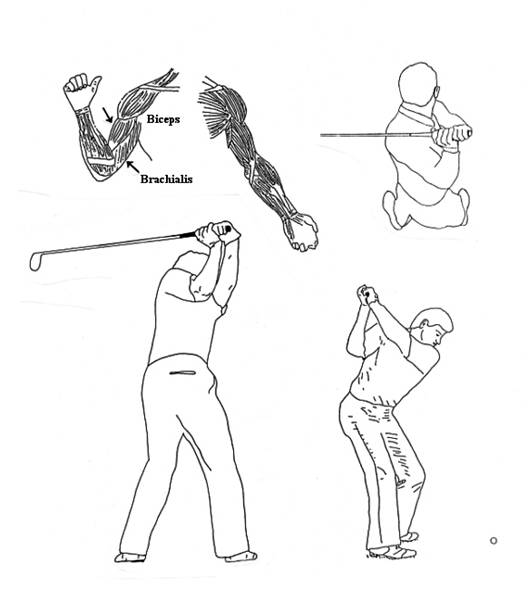

While the left arm remains nearly straight

during the backswing, the right arm folds upward and against the right side

(see Figure 5). The right arm gradually cocks up so that the right forearm is

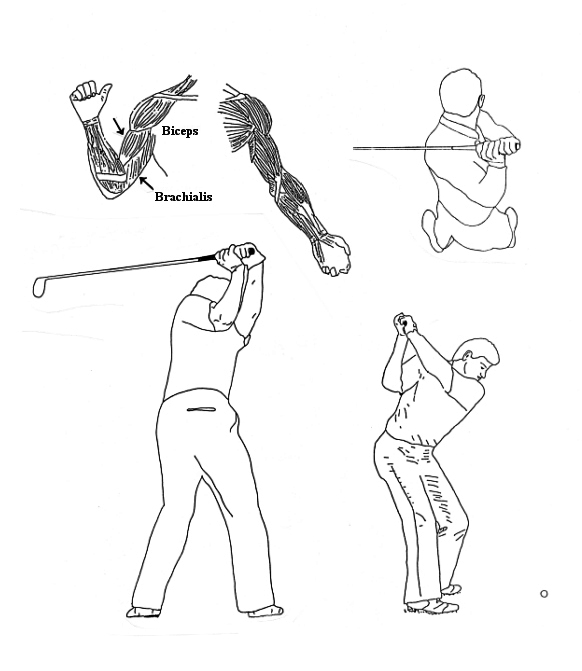

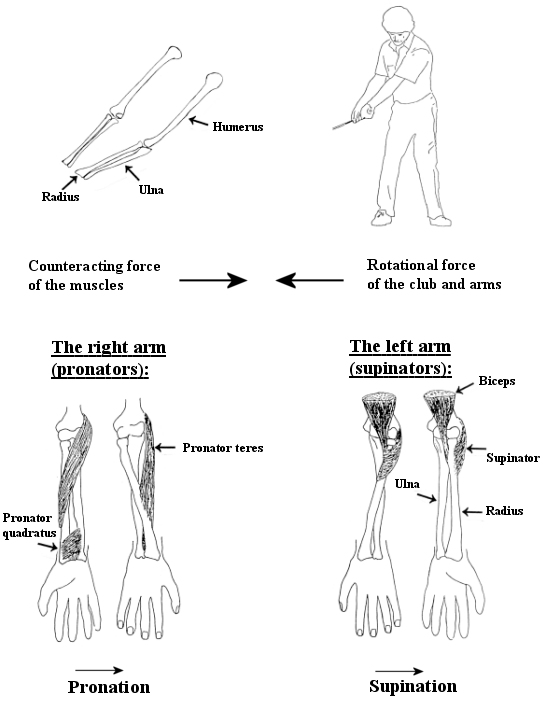

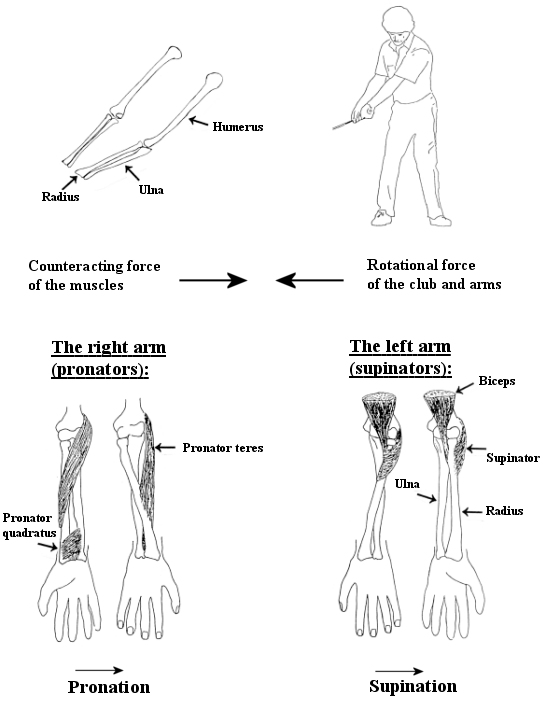

parallel with the shirt seam at the top of the swing. The Biceps and The

Brachialis are the primary muscles that flex, or fold, the right arm in the

golf swing. The Pronator muscles of the right forearm counteract the rotational

force that would otherwise turn the right hand and arm in a clockwise direction

(from the perspective of a right-handed person swinging the club). The Pronator

Teres pronates the upper-portion of the lower-right forearm, while the Pronator

Quadratus supplies the force to pronate the lower-portion of the right forearm

(near the wrist).

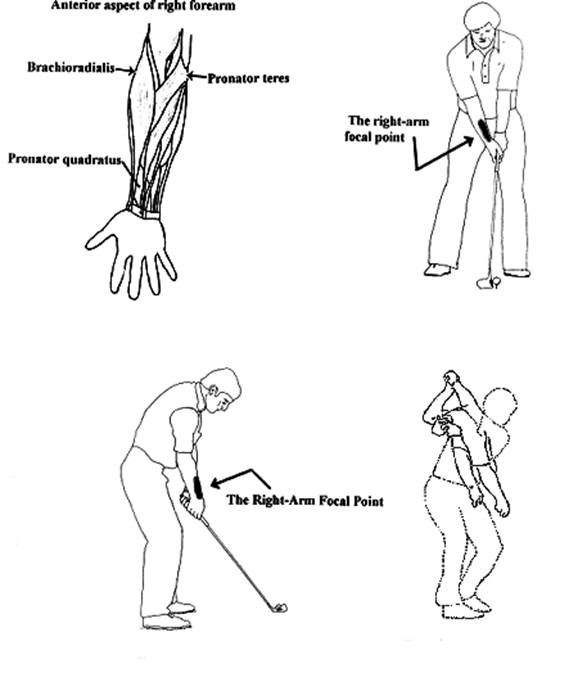

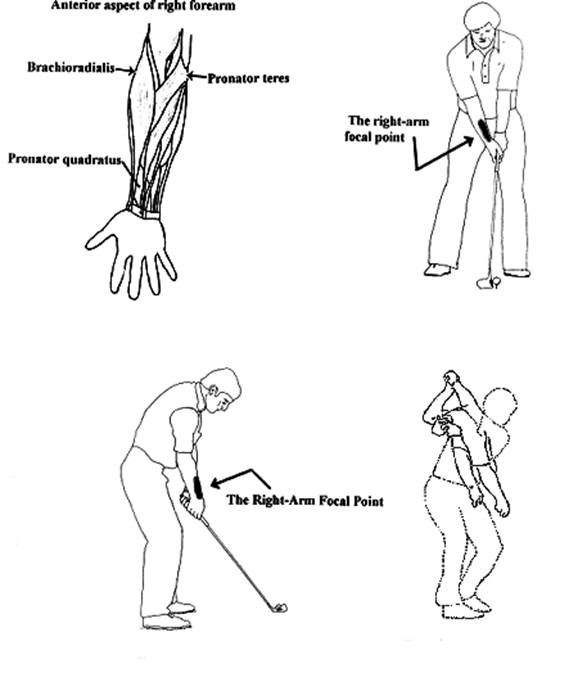

I focus upon an area near the

lower-to-middle portion of the right forearm, which ensures the correct folding

of the right arm. This region spans the lower-half of the forearm (from the

wrist to the middle of the forearm, or the inner and anterior aspect of the

forearm near the Flexor and Pronator muscles), and I visualize that it is above

the radius bone. Take the tip of your left-index finger and place it on top of

the radius bone of the right forearm, just above the wrist; next, while keeping

the index finger on this spot, place the tip of the left thumb on the top of

the radius bone at a position about half-way up the right forearm. I call this

region, between the index finger and the thumb, “the right-arm focal point.” In

fact, often I place the left index finger and the left thumb on my right

forearm, and visualize this area, before I swing the club. Also, I try to

"cock it up" on a path that will gradually get the right arm into the

desired position at the top. The correct folding of the right arm ensures a

“tight swing”, and maximum ball control.

This right-arm focus is effective because

it targets an area of the forearm that comprises the Flexor and Pronator

muscles. I discovered that these muscles act upon the forearm, the wrist, and

hand to counteract the forces that would otherwise move the right arm and

clubhead out of position during the backswing (this being for a right-handed

golfer). Without contraction, or tension, in these muscles, the backswing

forces would cause the right hand and arm to supinate (turn the hand and arm

over to the right, or turn the radius away from the ulna). Also, when the

Pronator muscles in this region are fixed (when the Radius is held in a fixed

position) they assist the other muscles in flexing (folding) the right forearm

upward. These muscles also help to counteract the tendency of the Biceps to

supinate the right forearm, when it flexes the right forearm upward.

When shots go astray, often it is due to

improper arm action. The arms must work together, and the easiest means to

ensure this is to use the inside muscles and to make sure that the arms are

held close together with the upper portions in contact with the upper torso. As

said previously, Ben Hogan visualized rope, or twine, wrapped around the arms

and also made sure that the upper portions of the arms were pressed against the

upper torso; these measures ensured a

“tight swing”, and very accurate golf

shots.

To train the arms to fold correctly, Sam

Snead advocates a drill in which he hits five-iron shots with his feet held

very close together. By concentrating on swinging around the fixed axis of the

spine in this manner, you can maximize accuracy because this trains for the

synchronization of the independent movements of the body and arms. This allows

you to “swing” the clubhead, rather than to use

leverage from some independent muscle movement. The great golf teacher,

Jimmy Ballard, called it ‘swinging the club with connection.’

While on the “arm-and-hand” subject, it is

also very important to note that these muscles should not be too over-worked

with weight training, or other forms of heavy work, that can result in a loss

of feel and flexibility. You should be able to feel the clubhead swing, but too

much bulk can get in the way of this process. In addition, when the arms become

too strong it impedes your ability to correctly fold the arms against the body

and to attain a unified swing. Jack Nicklaus was cognizant of the effect of too

much muscular work on his golf swing, and he abstained from such things as

heavy gardening for as much as two weeks before a major competition. Sam Snead would

cast his fishing rod with both hands for the fear that his swing would be

ruined by an overly-strong right hand. In his book, Power Golf, Ben

Hogan tells how “a well-known competitor” ruins his feel for the 1937

U.S. Open because he uses a hard rubber ball to strengthen his hands on the

train before arriving there. Lee Trevino has said that he was leery of giving,

or getting, a hard handshake on the first tee for fear of losing feel for the

club. These examples illustrate the importance of muscular “feel” and

flexibility in the game of golf.

To summarize, focusing in on the correct

movements of both arms ensures that the club is lifted in a precise and sound

manner, each time. These movements, combined with the rotator cuff movements,

are the desired movements that blend into a smooth, sound, and repeating swing.

In all three areas—the shoulders, and the left and right arms—we have focused

down to the anatomical level to achieve the highest degree of control over

these movements. This three-point focus allows us to control a tremendous

number of variables with only three swing thoughts. These are precise instructions to swing the

club, and the result should be great consistency. The goal is to practice these

movements so that they come together as part of a smooth, unhurried, swing on

the golf course. Several great pianists have also been known to train in this manner

by practicing the left-hand, and right-hand, parts separately, and then

combining the two into one fluid performance. The following sections will

present information and visualizations designed to further help in

understanding how to swing the club with these muscle groups.

-

Figure 3— Illustrations of left-arm action. The left

arm remains nearly straight, or fully extended, during the swing. The action is

best understood, and felt, by swinging the club with only the left hand and

arm.

Figure 4— Examples of set-up positions and

illustrations of the left-arm focal point. By taking the club back with the

left-arm focal point, one utilizes the correct muscles to get the left hand and

arm into the correct position at the top. The muscles at the back of the left

arm (The Anconeus and The Triceps) keep the left arm fully extended, or

straight; The muscles of the radial and posterior brachial regions ( all the

extensors and supinators) keep the club square by counteracting the rotational

force that would cause the left forearm to pronate, and arms to swing to the

inside of a “square” position. The Biceps Brachi and The Supinator are the

primary muscles that counteract the tendency of the left forearm to turn over

to the right.

Figure 5— Illustrations of right-arm action.

The right arm folds straight upward, while the upper portion remains close to

the side. The Biceps and The Brachialis muscles are primarily responsible for

the upward folding, or flexion, of the right arm. The Pronator Teres, and The

Pronator Quadratus, counteract the tendency of the right arm to supinate (turn

to the right) due to the rotational force of the arms and club; These muscles keep the bones of the forearm in a

position that is midway between supination and pronation. Also, The Pectoralis

Major is primarily responsible for keeping the upper portion of the right arm close to the right side.

Figure 6—

Illustrations of “the right-arm focal point,” right-arm action, and the muscles

of the anterior-side of the right forearm. During the backswing, the right arm

flexes upward while the upper-half remains close to the right side. The

Pronator teres and the Pronator quadratus keep the right arm from turning over

to the right, and thus opening the clubface. I’ve found that I can ensure the

correct right-arm action by concentrating on the action of the right arm, and

by zeroing in on “the right-arm focal point.” Although I refer to this region

of the right arm as a point, it is an area that spans the lower-half of the

forearm. I think of this as straight-line area that runs along the radius bone

(the portion where the radius is closest to the skin’s surface).

Figure 7— Frontal

and side views, showing positions of the hands and arms at several phases

during the backswing. The left arm remains fully extended, which gives the

swing a constant radius and allows the golfer to consistently return back to

the ball on the downswing. The right arm cocks upward and remains close to the

right side. The correct execution of these movements will place the club in a

“parallel position” (to the target line) at the top of the swing.

Figure 8— Anatomical

illustrations of various muscles of the left arm, the right arm, and the

shoulder areas. By understanding the exact location and function of many of

these important muscles, one can focus upon these areas to ensure success. Like

concert pianists, who practice and understand the role of each hand, the golfer

should practice and understand the movement of each arm. In addition, the

golfer should practice and understand the rotational movement produced by the

rotator cuff muscles of the shoulders. These three areas become a three-point

focus which is the secret to a sound swing and tremendous consistency—it is the

foundation of “The Redemptive Golf Swing.” Such concepts as lower-body movement

(e.g., weight shift, etc.), constant spine angle, keeping the head still and

behind the ball, and many others, have been practiced for many years and have

become “second nature” (or at least, subconscious); thus, we are able to narrow

our focus to these three crucial areas (the left and right arms, and the

shoulders). These three areas are often vaguely understood and by focusing down

to the anatomical level—muscle groups and their specific functions—we gain great

control to produce a sound swing.

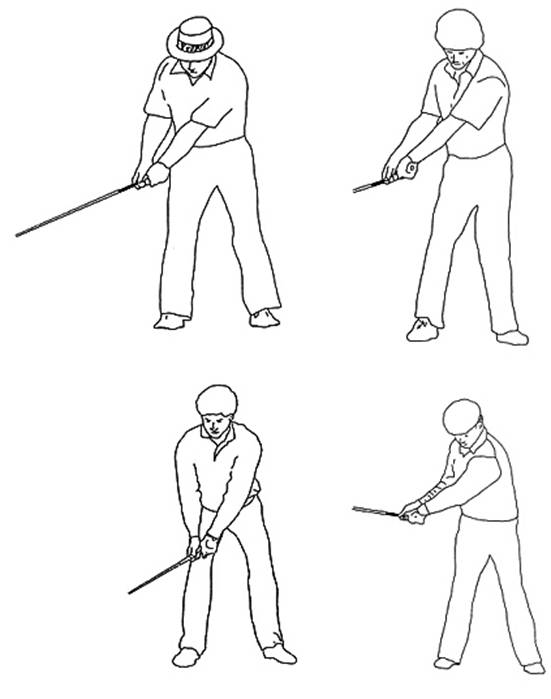

Figure 9—Illustrations

of the takeaway. The shoulders, hands, and arms move back together to form what

is called a “one-piece takeaway.” In this manner, the grip-end of the club

should point toward the center of the body (stomach, sternum, etc.) during the

initial stages before the club moves up and around the body. The club starts

backward with a simultaneous shifting of the weight from the left foot to the

right foot, while the shoulders turn freely around the fixed axis of the spine.

At the start of the swing, the rotator cuffs turn the shoulders, while the

hands and arms retain the same relative position to the shoulders as at

address. It is not until after this first part of the swing—“the one-piece

takeaway”—that the arms begin to lift the club to the final position at the top

of the backswing.

Figure 10—

Illustrations of the lower-arm action. During the initial stages of the

takeaway, the arms should maintain the same relative address positions. The

rotational force of the arms and the club will impel the left arm to pronate

and the right arm to supinate. However, the muscles of the left, and right,

arms counteract these forces. In other words, during the early stages of the

backswing, the Supinator and Pronator muscles act to keep the Radius and Ulna

bones from moving out of position.

The Legs And Feet

(Lower Body Action):

If you read a good portion of the

instructional material, you will find a wide number of explanations on how the

club starts backward during the first part of the backswing. “The one-piece

takeaway” is probably the most common explanation, meaning that everything

(hands, arms, shoulders, the left knee, etc.) starts back together, or in

unison. Also, the rebound from the forward press is widely cited as the initial

force, or movement, that starts the clubhead moving backward.

Do you initiate the backswing with the

upper-half of the body, or the lower-half? There are schools, or “camps,” that

advocate one way, or the other—and even that both halves are the origin of the

initial movements. Although some schools teach that the legs and feet serve

strictly as a base of support for the upper-body, others strongly cite the

action of the feet and legs as being responsible for the initiation of a sound

backswing. Harry Cooper says, “the cardinal sin in golf is making the initial

move from the waist up.” Jimmy Ballard advocates a “rhythmic kick of the left

foot and knee.” Johnny Miller explains the initiation of his swing as “a rock forward,

rock back move” of the knees. Bobby Jones attributes the take off, or beginning

of the backswing, to the action of the left foot. In his book, The Education Of A Golfer, Sam

Snead emphasizes the importance of the feet when he helps a “slumping” Toney

Penna by advising him to take the club back, and to control everything, with

his feet. Also, Jack Grout and Jack Nicklaus emphasize “lively feet” as an

essential part of the swing. These examples illustrate the important role of

the feet and legs when swinging a golf club.

During the backswing, the majority of the

weight must shift from the inside of the left foot to the inside of the right

foot; this weight then must shift back to the inside of the left foot during

the downswing. Also, while making this weight shift the legs must maintain the

same relative degree of flex as at address (or it wouldn’t be possible to

consistently return to the ball). Thus, the muscles of the feet and legs are

very active during the swing and the action must occur in a very coordinated

manner to produce the desired results. In actuality, the weight shift is a

balancing act in which the leg muscles contract, or become fixed, to

accommodate the shifting weight (e.g., the right leg muscles become fixed to

accommodate the increased load that is placed upon them, during the backswing

for a right-handed golfer). In other words, when the center of gravity is

shifted backward during the backswing, the muscles on the right side are

stressed to maintain balance and position; when the center of gravity is

shifted forward (to the left during the forwardswing), the muscles on the left

side are stressed to maintain balance and position.

Previously, we talked about turning around

the central axis, or straight spine. Many golfers achieve this concept with the

hub-and-wheel visualization: the neck, head, or spine is the hub, and the

clubhead turns around in the same arc and plane as the outer-rim, or spokes.

Many teach this turning-around-the-central axis concept by asking their students

to visualize a weight on the end of a string that is swinging around on the

same plane; the weight represents the clubhead, and the center of the arc

represents the spine, or neck.

With the hub-of-the-wheel and the

weight-and-string visualizations, there is only one axis, or pivot point.

However, to avoid problems with these visualizations we must understand that we

turn by shifting the weight onto the right hip, and then back to the left hip.

Thus, there must be some form of lateral shift to achieve this.

At the start of the backswing, you should

focus on the action of the feet and legs to ensure a consistent and effective

takeaway. Visualizing the action of the legs condenses many fundamentals into

one central focus, which allows you to accomplish several tasks: First, it

ensures the proper weight shift and a smooth takeaway; Second, it allows you to

keep the constant radius of the swing which is vital to consistency; Third, it

allows you to take the club back in the same manner each time and to achieve

“the one-piece take-away,” by providing “a cue” for the muscles of the

upper-body to perform their function. Finally, this allows you to “build-up” a

swing momentum and centrifugal force so that you accelerate through the ball at

impact. As with the arms, you should

focus on using the inside muscles. The essential problem is that the swing is a

rotational movement around a fixed axis, the spine, but it has to be achieve by

shifting the weight amongst two points, which are the hips.

To update, we now have two main areas of

focus: 1.) The action of the feet and legs, and 2.) The three-point focus (the

shoulders, and the left and right arms). It is important to have a clear

visualization of these movements in your mind; study them while swinging a golf

club, and watch professionals swing on television, or video.

References: Snead,

Sam. The Education Of A Golfer. 1962. Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Rockefeller Center, 630 Fifth Avenue

New York 20, N.Y.