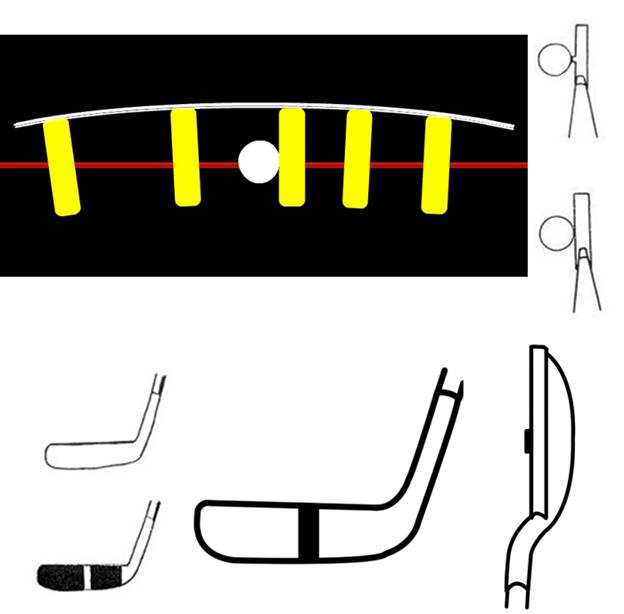

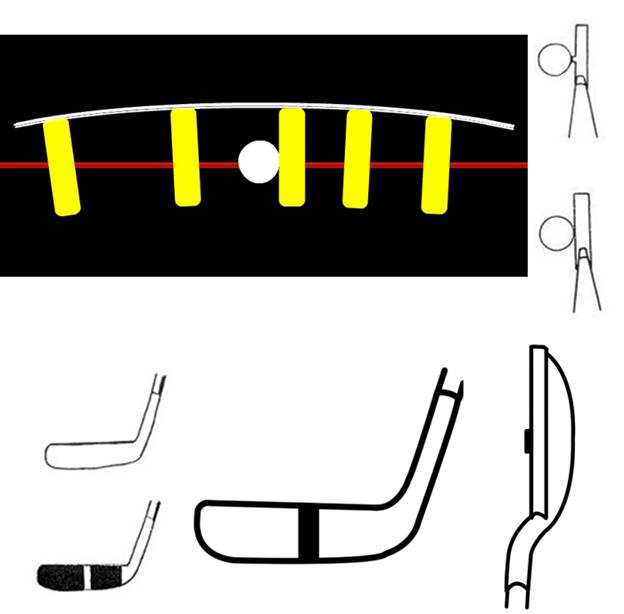

Figure 21—

Illustrations of “the altered-putter” concept. All varieties of putters are

possible, with the common characteristic being the altered putter face. A small

portion, or strip, of the original clubface is left to contact the ball.

Attempting to hit the ball on this small area will result in an on-line stroke

that does not “break down” through the hitting area. Completion of the

visualization fulfills the older swing thought of “continuing the putter toward

the hole.” Below are additional putter styles.

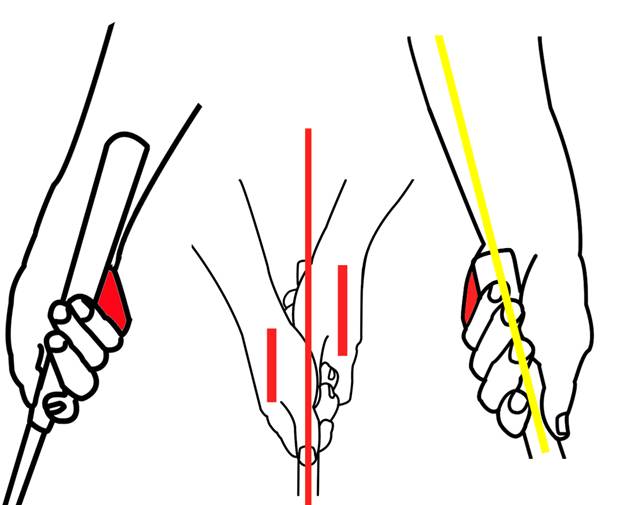

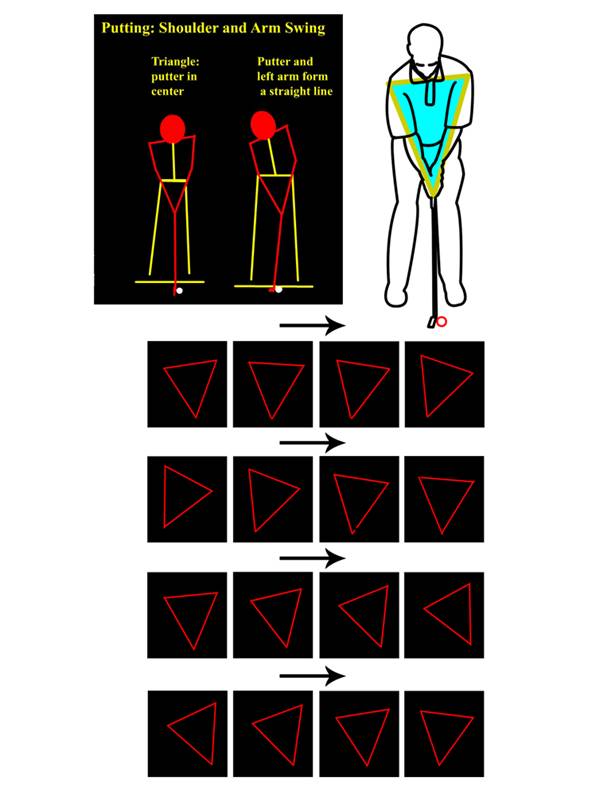

Figure 22—

Illustration of the arc and path of the putterhead. Like the clubhead in the

fullswing, the putterhead travels along

a smooth arc. The shoulders rotate the putter backward, while the job of

the arms, hands, and wrists is to maintain the address dynamics; that is, the

shoulders supply the force to hit the ball forward, and the arms, hands, and

wrists keep the putter in a “square” position throughout the stroke.

The arc of the putter does come slightly

up (off of the putting surface), as a result of the angle at which the

shoulders rotate.

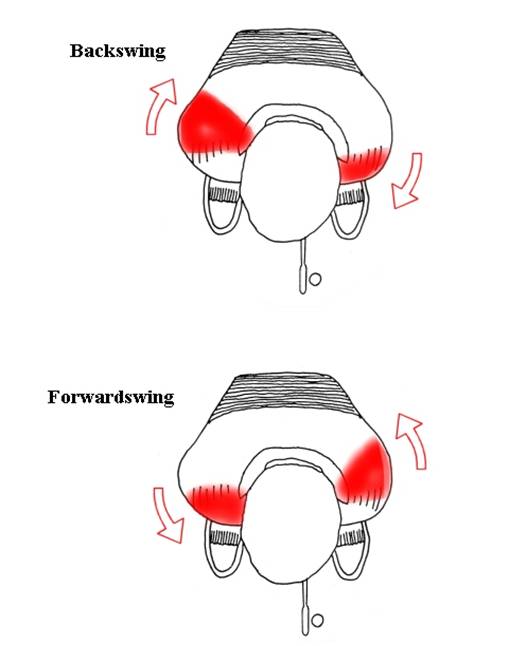

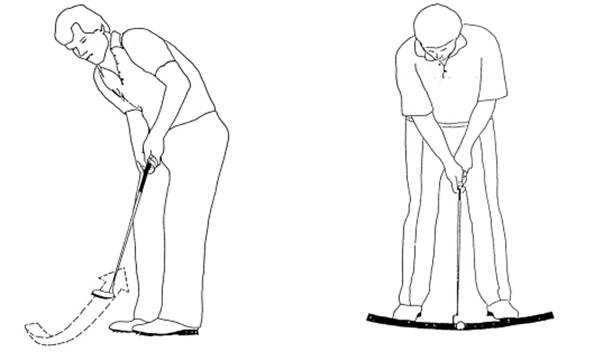

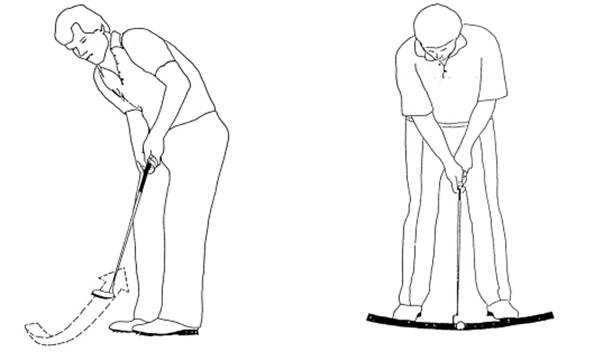

Figure 23—

Illustration of the putting stroke from directly behind. Many golfers visualize

swinging the putterhead straight back and through. However, the inclination and

rotation of the shoulders gives the putterhead an arc that comes upward (off

the ground) and inside the line of the putt. Sound execution of the putting

stroke will bring the putterhead up a slight plane, as illustrated.

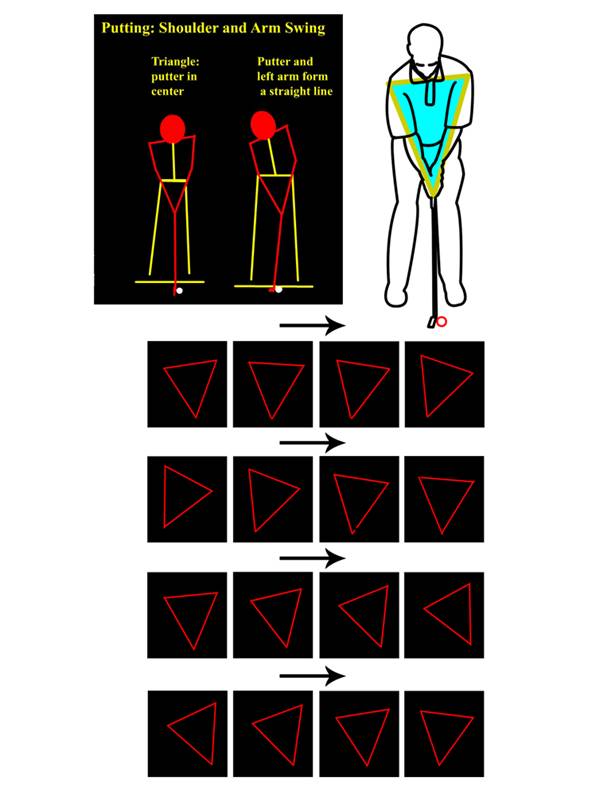

Figure

23a—

Illustration of the triangle formed by the shoulders and hands. If you try to

maintain the triangle during the course of the stroke everything will be

steady, which will produce a consistent stroke.

Competition/Playing

“Under Pressure”:

“When baby needs a

new pair of shoes,

it can alter anybody’s

thinking.”

—Tony Lema

Playing “under pressure” is a phrase to

describe situations when one has more “at stake” than in the average every-day

situation; these situations can range from playing in the U.S. Open, to just

wanting to avoid embarrassment in front of other people. When one becomes

fearful, or anxious, the muscles become tense, movements become quick and

jerky, and mental acuity decreases—all reactions that are deleterious to one’s

golf game! Arnold Palmer emphasized the importance of the mental aspect in golf

when he said, “I have to hold that confidence is 90-percent of the game...You

have to develop a mental approach that will always insure that you will never

beat yourself...”

Research studies to pinpoint the reasons

that some people are able to handle high-pressure motor-skill tasks (such as

putting under stress) better than others, show that trained athletes are more

able to handle the pressure because of their mental strategies which decrease,

or minimize, the physiological effects of the stress. Somewhere in their brains

are neural pathways—formed from experience, learning, and creativity—that

produce thinking options to deal with the situation, and to perform calmly and

confidently the task at hand; that is, these athletes switch on thoughts that

help to successfully negotiate the situation. These trained athletes have had

many previous experiences with such stressful situations, and thus have gained

valuable insight and confidence that one can only gain through such

experiences.

“Choking” is the term that we use when

someone does not successfully perform a task, which is fairly routine, when

under increased pressure; even the simplest task, becomes very difficult when

one’s mind is full of doubt, the knees shake, the heart pounds at nearly 120

beats per minute, and one’s level of concentration is severely affected! The

best athletes take measures to prevent, and to control, these bodily reactions

so that they can perform at the highest levels. They have learned to prevent,

or to stop, the deleterious effects of the nervous reactions, usually by

looking at the situation in an objective, rational, manner and by concentrating

on lines of thought which are directed toward the positive aspects of their

ability.

In an interview a number of years back,

Jim Colbert was asked the reasons behind his tremendous success on the Senior

PGA Tour (he earned about 1.7 million dollars as a 25-year member of the PGA

Tour, and about 8 million dollars in six years on the Senior PGA Tour). In

addition to finding therapies to help his ailing back, Jim attributed help from

Jimmy Ballard, whom he met in his mid-thirties, which profoundly improved his ball-striking

ability. When asked about the reasons behind his tremendous putting ability,

Colbert alluded to being able to channel that energy of nervousness into the

job at hand. According to Colbert, those moments when athletes do really

special things come from that high-aware state, or nervousness, that athletes

experience when they are in high-pressure situations. In other words, Jim learned

to take a positive view of the nervousness, and not to wish it away because he

knows that it will push his play to a higher level. In those years while

playing on the Senior Tour, Jim Colbert played some of the best and most

consistent tournament-golf ever seen—the culmination of decades of

trial-and-error learning to perform at his best both physically, and mentally!

We all loath the feelings and bodily

reactions associated with high-pressure situations, but our mind-set about the

situation usually determines how far these bodily reactions go and how

successfully we are able to handle the situation. Dow Finsterwald said the

following about how he learned to deal with the pressure of tournament golf:

“What I’ve managed to do...is learn to face

and accept the inevitable out

there. Sure I hear the noises,

but I have pulled their teeth by expecting

them. By reconciling myself to

many things that are inevitable at a

tournament which is supported and

attended by the public, I have pretty

well eliminated their power to

disturb me”.

Finsterwald

learned to overcome the pressure by expecting it, and accepting it, as part of

the job of being a tournament professional. By accepting it, rather than

wishing it away or running away from it, he gained control over it and was able

to play his best golf.

Golf is a game of precision, but it’s not

good practice to worry, or criticize, the condition of your swing on the golf

course. You can only work with what you have at the moment, and you’ve got to

make the best of it! After he turned

professional, Doug Ford received some very important advice from his father:

“He knew my swing wasn’t much to look at, but he insisted it was good enough.”

His father knew how easy it was to get lost in worry about one’s swing

technique, and how important it was to free the mind from this doubt so that

one can concentrate on the task at hand. The tension that this line of thought

can cause, is deadly to the relaxation and concentration that is necessary to

play “at one’s best.”

Byron Nelson, known as one of the greatest

players of all time and for his record of 11 tournament victories in a row,

said:

“When you’re in

competition, scoring is a game of it’s own,

and if you have to

concentrate on your swing, the pressure

is magnified a thousand

times.”

According

to Nelson, the touring professionals of his time practiced very little at the

important tournaments—just enough to warm up—because they wanted to concentrate

on strategy, and avoid the added burden of worrying about the condition of

their swings. Nelson said that one must master the mechanics of the game,

practice incessantly so that they become second-nature, and continue to

practice to stay in “this groove.” This practice will carry over onto the

course, and enable you to play without having to worry too much about your

swing.

Today, there is a great deal of emphasis

on the “pre-shot routine,” a step-by-step mental checklist that the golfer

completes before each shot. Gene Sarazen advocated the use of a pre-shot

routine, as “the best way to overcome the jitters.” According to Sarazen, by

concentrating on the elements of this routine (taking the stance and other

set-up factors, visualizing and thinking about the shot, etc.) one does not

have time to get shaky nerves. Most of the successful thought strategies that

highly-trained athletes employ to deal with stressful situations serve to not

only ensure the likelihood of producing the desired result, but they also can

be thought of as distractions to prevent the mind from focusing on thoughts

that could make one nervous and tense. The human mind can only focus on so many

things at once, and you can learn to work this toward your advantage in

stressful situations!

J. Douglas Edgar, while playing with Tommy

Armour in the French Open, was showing signs of extreme nervousness which was

affecting his play. Armour turned to Edgar and said, “Why don’t you hum a tune,

or whistle, old chap, and get your mind off this damned thing?” Edgar took

Armour’s advice, and he went on to win the tournament. Noticing his constant

whistling, the Frenchmen called him “The Whistling Champion.” His focus was

redirected toward the whistling, and away from the thoughts that were causing

him to be nervous. Edgar also believed that his idea, “the gate”, worked

because it served as a mental distraction that focused the mind on “the movement”

and away from worry “over an infinity of details.”

The information and the procedures

involved in The Redemptive Golf Swing and The Composite Putting System have all

been designed to prevent one from being affected by “nerves.” The

anxiety-preventative aspects are the following: First, this knowledge, or

insight, breeds great confidence to perform the job at hand because you have a

first-rate system that will allow you to successfully negotiate the situation;

Second, focusing on the procedures and check-points funnels your thoughts and

prevents you from focusing on things that could result in nervousness and

tension; Third, the concisely organized procedures of this system allow you

time to consider other factors, such as course management. Over time, the mere

thought of this system should take care of those old doubts, and worry, that

plague most golfers on the golf course.

When you get nervous, it’s because you

don’t have “muscle memory”.

The

Redemptive Golf System:

Combining the most advanced research in

learning and memory technology,

physiological psychology, and

kinesiological research to achieve the highest

degree of swing mastery and swing

consistency that has ever been achieved !

Recent research shows that complex

movements such as the golf swing,

which are composed of a series of smaller movements, can have an

incorrect segment “clipped out” and

replaced with the correct movement

through several techniques. This

correct sequence of movements is then

stored in the cerebellum, and motor

centers of the brain, and can

be called forth to produce a correct

swing at normal speed on the golf course.

This is analogous to putting together a

film, frame by frame, and then

seeing the desired result when playing

it at full speed. This “muscle memory"

is actually brain, or cerebellum,

memory.

About

the Author:

Dan Blevins is a graduate of Earlham

College (Richmond, Indiana) with a

degree in Biology, and California State

University (Fullerton, Calif.) with a

degree in psychology. A four-sport

varsity letterer in college (track,

cross-country, baseball, and golf), the

four years that he played varsity

golf sparked the beginnings of his

intense interest and search to develop a

golf system that would allow him to

consistently play at his best. An avid

reader, he used his knowledge in human

anatomy/physiology, psychology,

and movement studies, to finally

piece-together the system that he had been

looking for all those years. During his

senior year in college, Dan was

the recipient of the Wendel M. Stanley

Senior-Scholar Athlete Award, named

after the the school's 1946 Nobel Prize

winner and which carried the

condition of being an outstanding

athlete with an extremely high level of

academic achievement (3.4 overall GPA

or higher). A resident of Anaheim,

California, he has worked both in

business and as a teacher in the Anaheim

Union High School District while

teaching such subjects as Chemistry,

AP Physics, and advanced math. As a

substitute teacher, he had the unbelievable coincidence of having Tiger Woods

in many classes when Tigerattended Orangeview Junior High and Western High

School which are both inthe Anaheim Union High School District. His father,

Harold Blevins, was born in Topeka, Kansas, and is a cousin of 5-time British

Open winner,

Tom Watson, through his grandmother

whose last name was also Watson.

Dan modeled his putting stroke after

Watson's, which produces deftly accurate results, and he describes it as being

like a person with a "modern, high-precision, scoped rifle versus others

who are using 18th Century muskets."